Okay, so I got interested in figuring out how those weather balloons actually do their thing. You see them mentioned, but the nuts and bolts were a bit fuzzy to me. So, I decided to dig in and piece together the process, like I was doing it myself.

Getting the Parts Together

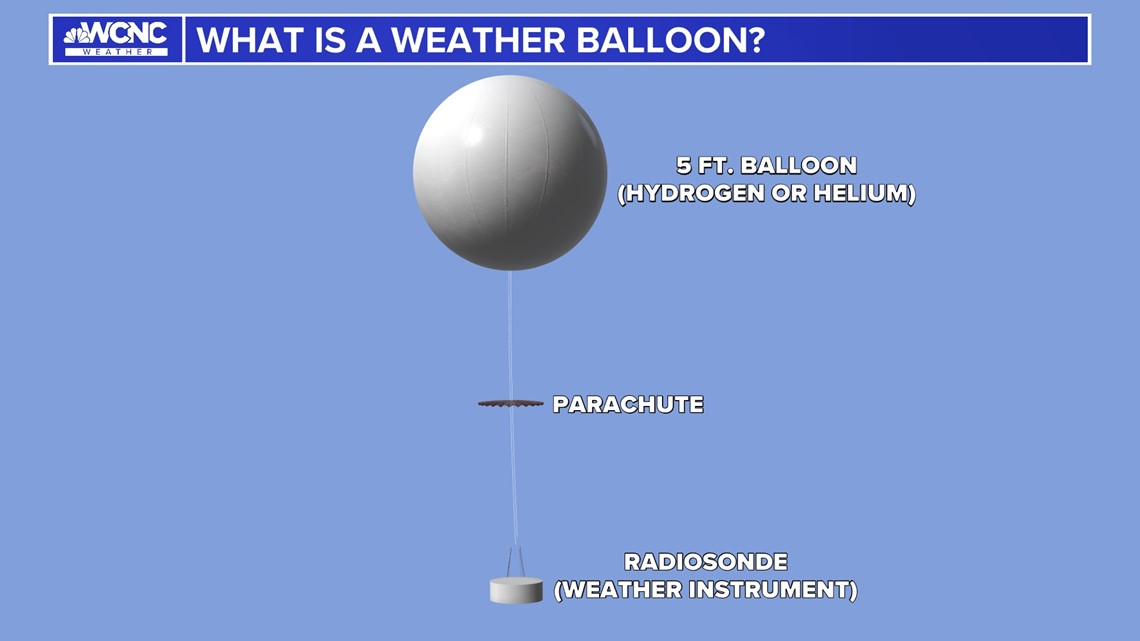

First off, I imagined getting the main components. You obviously need the balloon itself. Turns out these aren’t your average party balloons. They’re usually made of latex or a synthetic rubber, designed to stretch big time.

Then there’s the gas. You need something lighter than air to make it go up. Most often, it’s helium, sometimes hydrogen, though hydrogen’s a bit trickier because it’s flammable. Gotta get a tank of that stuff.

The most important bit, really, is the instrument package. They call it a radiosonde. It’s a small, usually white box that hangs below the balloon. This little guy is the brains of the operation. Inside, it typically has sensors for:

- Temperature

- Air pressure

- Humidity

- GPS (to track its location and calculate wind speed/direction)

And finally, you need a string or cord to connect the radiosonde to the balloon, and often a parachute. The parachute is crucial for when the balloon eventually pops, so the instrument box doesn’t just plummet.

Putting it to Work (The Process)

Alright, so picture this: you take the folded-up balloon out. Carefully, you attach the nozzle from the gas tank and start filling it. You don’t fill it completely tight like a party balloon on the ground; you leave room for it to expand as it goes higher where the air pressure is lower. It gets pretty big, even on the ground.

Next, you get the radiosonde ready. Check the batteries, make sure the sensors are okay. You tie it securely to one end of the cord. Then you attach the parachute along the cord, usually between the balloon and the radiosonde.

Once the balloon is filled enough and everything’s tied together – the balloon, the parachute, the radiosonde – you’re ready for the release. This part requires a bit of care, especially if it’s windy. You carry the whole setup out to an open area.

Liftoff and the Job

Then, you just… let go. The balloon immediately starts rising, pulling the parachute and the radiosonde up with it. It ascends pretty fast, climbing thousands of feet.

As it goes up, the radiosonde is constantly working. The sensors are measuring the conditions at different altitudes. The thermometer checks the temperature, the barometer measures pressure (which helps figure out altitude too), the hygrometer measures moisture, and the GPS tracks its path.

Crucially, the radiosonde has a small radio transmitter inside. It sends all this data back down to a receiving station on the ground in real-time. That’s how weather folks get the information they need for forecasting – they get a profile of the atmosphere.

The End of the Journey

The balloon keeps rising and expanding as the outside air pressure drops. Eventually, high up in the atmosphere (like, way up there, maybe 100,000 feet or more), the balloon material stretches to its limit and it bursts.

This is where the parachute comes in. It opens up and allows the radiosonde to float back down to Earth at a much slower, safer speed. Sometimes people find these landed radiosondes, often with instructions on them for returning them so they can be reused.

So, that’s the whole cycle I pieced together. It’s a relatively simple concept – float some sensors up, get the data back via radio, let it come down. But doing it day in, day out, all over the world? That gives us a vital picture of the weather brewing up there. Pretty neat, once you walk through the steps.